Gluck/Wagner: Iphigenia in Aulis

CD Review by Tim Ashley

Gluck: Iphigénie en Aulide

DVD Review by John operaramblings.wordpress. com

Christoph Willibald Gluck: the composer who deserves better

By Rupert Christiansen

Gluck/Wagner: Iphigenia in Aulis - CD Review by Tim Ashley, theguardian.com/au 10 April 2014

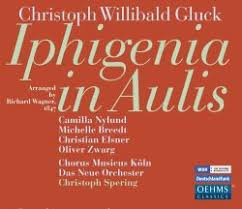

Nylund/Breedt/Elsner/Zwarg/ Chorus Musicus/Köln/Das Neue/ Orchester/Spering (Oehms)

This is a beautiful set, but a curious one. Its release marks the tercentenary of Gluck’s birth, an anniversary that hasn’t as yet, in the UK at any rate, received anything like the attention it is due. However, deriving from a German radio production in April last year, this brings another, altogether more prominent anniversary into the frame – what we have here is not Gluck’s original Iphigénie en Aulide, first heard in Paris in 1774, but a German-language version prepared by Wagner for performance in Dresden in 1847.

That Wagner should be drawn to Gluck was inevitable. The latter’s revolutionary demands for a total work of art comprising drama, song and dance, conveyed in music of absolute directness, pre-empt Wagnerian aesthetics. Of all Gluck’s operas, it is Iphigénie en Aulide – with its conflicts between human love and divine proscription, and its redemptive heroine willing to sacrifice herself for the greater good – that fits most closely with Wagner’s preoccupations.

But unlike Berlioz, whose edition of Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridicestill forms the basis of many modern performing versions, Wagner distorts as much as he adapts, and in streamlining Gluck, narrows his range. Dance is integral to Gluck’s synthesis, but Wagner cuts the ballet. Passages are re-written to blur the divisions between recitative and aria way beyond Gluck’s original intentions. Wagner, chameleon-like, never strays beyond Gluck’s harmonic scheme, though his re- orchestration, beefed up with extra wind and brass, sounds Beethovenian at times.

Handsomely conducted by Christoph Spering, and boasting some terrific choral singing from the Chorus Musical Köln, the recording is very fine. The great performance comes from Oliver Zwarg as Agamemnon, dignified, anguished and trapped, Wotan-like, in a hell of his own making. Christian Elsner’s Achilles is nicely pitched between hero and bully-boy. Michelle Breedt’s Clytemnestra could do with more elemental rage, but Camilla Nylund makes a fine Iphigenia, radiant and noble rather put-upon and father-fixated. It remains, however, something of a wasted opportunity. Wagner's Iphigenia is just not as good as Gluck›s, a new recording of which would have been infinitely preferable.

Gluck: Iphigénie en Aulide

DVD Review by John operaramblings.wordpress. com

Posted on April 5, 2013

Gluck’s Iphigénie en Aulide is finally available on Blu-ray and DVD. It was staged and recorded as a double bill with Iphigénie en Tauride at De Nederlandse Opera in September 2011 in productions by Pierre Audi. It’s excellent in just about every respect. The cast is to die for, the production is interesting and so is the staging in the rather challenging space of The Amsterdam Music Theatre, which also poses problems for the video director. Backed up, on Blu-ray, by a 1080i picture and DTS- HD-MA sound it’s a pretty compelling package.

Gluck’s libretto is based fairly closely on the Euripides play though Menelaus and Orestes are cut and it ends with the assumed, non-extant, ending where Diana forgives everyone and reunites the lovers rather than spiriting Iphigenia off to Tauris. Audi sets the production in, more or less, the present. The Greek soldiers wear combat gear, Agamemnon wears the dress uniform of a high ranking officer and Iphigenia and Clytemnestra wear rather fetching camo couture, except in the final scenes where Iphigenia seems to be wearing a suicide bomber belt. The set is a bare stage with metallic staircases rising either side. The orchestra is behind the stage and beyond them is a gallery that isn’t used much though it has a role to play in the final scene. It’s simple and effective and allows the audience to focus on the characters.

The cast, as I said earlier, is amazing. Véronique Gens sings the title role with Anne-Sofie von Otter as Clytemnestra. Fréderic Antoun is Achilles and Nicolas Testé sings Agamemnon. All four sing and act superbly. All four characters are utterly believable; the father and daughter torn between love and duty, the distraught, yet dignified queen and the dashing and impulsive young hero. It’s a timeless story effectively told. And the music is just gorgeous. The main characters are well backed up by the rest of the cast, with an especially fine cameo by Christian Helmer as Calchas, and by the off-stage chorus. Marc Minkowski and Les Musiciens du Louvre, Grenoble provide suitably idiomatic direction and accompaniment.

I’m not sure what to make of Misjel Vermeiren’s video direction. It’s a challenging set to film, not helped by low lighting levels. He responds by using a lot of weird camera angles, including directly overhead, and a lot of close ups. Ultimately it doesn’t matter too much as the glory here is the singing and the acting rather than the staging. The picture and sound quality (surround and stereo) are both first class. There is a short bonus interview with Audi on the disk and a synopsis and essay in the booklet, but no track listing. Subtitles are English, French, German, Dutch and Korean.

Christoph Willibald Gluck: the composer who deserves better

Rupert Christiansen asks why Gluck’s tercentenary will pass by largely unheralded in 2014 telegraph.co.uk 05 Jan 2014

Opera lovers had a bumper time of it in 2013, with jamborees marking the centenaries of three great masters Britten, Verdi and Wagner. This year (2014) it’s a shame that we’re not celebrating equally loudly the 300th birthday of another composer whose importance to the development of the art form can hardly be over-stated – Christoph Willibald Gluck, born in an obscure German principality near Nuremberg in 1714.

Apart from Orfeo ed Euridice – or rather its Housewives’ Choice favourite “Che faro?”, as sung by Kathleen Ferrier – nothing by Gluck has ever been widely popular and he will doubtless always remain a specialist taste. One can immediately hear why: his greatest music is marked by a measured dignity that doesn’t offer easy entertainment or sensual charm for audiences craving instant gratification. A reformer by nature and a neo-classicist at heart, he deplored the florid excesses and amorous intrigues of conventional 18th-century opera and aspired in works such as Iphigénie en Tauride and Alceste to return to something redolent of the moral and spiritual grandeur of Greek tragedy.

Rather than showy arias designed to show off prima donnas’ techniques framed by fanciful plots, Gluck cultivated a purified style shaped by expressive declamation, dramatic dialogues and solemn choruses, underpinned by simple orchestration and unchromatic harmonies.

He could write wonderfully rich melodies too (emanating from the throat of a Régine Crespin, the aria “O malheureuse Iphigénie” from Iphigénie en Tauride can be even more heart-rending than Orfeo’s “Che faro?”), but they are conceived not as applause-seeking highlights so much as soliloquies charged with emotional and spiritual intensity. One might sum it up by saying that Gluck took opera seriously.

As a result, his writings as well as his scores have certainly been of enormous influence: on Mozart in Idomeneo and the Masonic passages in Die Zauberflöte; on Rossini in his serious operas; on the Berlioz of Les Troyens, on Wagner in his

quest for the high moral ground. Yet today, even though his modestly scaled works are relatively inexpensive to mount and easy to cast, opera houses seem to shy away.

There are reasons for this. The absence of any sensational element means that he’s not good box office, and modern producers don’t know how to handle such spare and chaste material. Another drawback, baffling to our contemporary sensibility, is his habit of arbitrarily introducing a God ex machina to resolve tragic dilemmas in his final scenes.

One notable recent attempt to grapple with these problems was made by the late German choreographer Pina Bausch, whose danced versions of Orfeo and Iphigénie en Tauridecarried considerable force and gave the dramas a new theatrical dimension.

But it’s sad that at his tercentenary, the oeuvre of this seminal figure isn’t being explored in any depth and that a major operatic institution such as Glyndebourne hasn’t had the courage to honour his achievement by engaging the likes of Sarah Connolly or Alice Coote – superb Gluckian interpreters both – for the title-roles of Alceste or Iphigénie en Tauride.