By Robert Lloy

Katherina Wagner’s 'Die Meistersinger' - The Final Wrap!

Having been handed the baton held since 1966 by her Father Wolfgang, Katherina Wagner has inherited a position of great influence and authority. Although sharing the administrative responsibilities as an Opera Director, it falls on her to maintain the creative standards that have made the Bayreuth Festival unique in the musical world. As I see it, her duty of care is to uphold the status of the Festival, enhance its prestige and, above all, safeguard its survival in the challenging, uncertain world of the 2Ist century. With respect for the past, the new and exciting advances in today’s technology allow an almost unlimited freedom of expression. Like the members of her illustrious family who have preceded her, Katherina Wagner faces unpredictable obstacles—none more than Richard Wagner himself. Each has needed to establish their personal imprimatur on the Festival—expand its sphere of influence while keeping the Wagner repertoire always innovative and constantly refreshed.

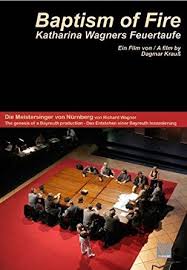

Before viewing the “Baptism of Fire” documentary and knowing nothing of her credentials, I anticipated a fresh, new broom approach— a young Director’s interpretation. At the same time, I feared her interpretation might be dripping with stultifying reverential awe. Either way, I needn’t have worried! Aware that first impressions can be misleading, the engrossing “Baptism of Fire” alerted me to the shock tactics she employed to present her iconoclastic, insensitive offering. With culpable indifference and questionable taste, Katherina Wagner has marshalled the worst aspects of today’s popular culture in trying to “communicate” and be relevant to a so-called modern audience. Having now seen the entire production on DVD, I feel more entitled to express what is a very personal view—one which I hope will be challenged with passion.

Surely it is the timeless universality of the Wagner repertoire that encourages new exploration and freedom of interpretation. The foundation, the Director’s starting point, is the score: the orchestration answers every question. To impose a too rigid or fixed concept is to conflict with the basic musical structure. Whether viewing a DVD screening or attending a live performance, this balance between score and interpretation is especially important if it happens to be an audience member’s first experience of the work. Right or wrong, good or bad— the impression left is usually indelible, possibly damaging. Evaluating the merit of a given production—either as a shared experience surrounded by the collective energy of fellow Audience member, or on DVD as a record of the performance, restricted by stage lighting and selective camera work—we are dealing with two quite different productions. In this case, it is only on the DVD that I can make any judgement.

Katie French’s excellent and informative article in our last Newsletter pointed out these details with great perception and clarity. Having the advantage of attending the Production in the Festspielhaus, she experienced much in Katherina Wagner’s production that pleased her and thus was able to make a valuable comparison. My appreciation of her opinion has tempered my extreme reaction into a manageable and enjoyable outrage.

Long after this production has been removed from the Festspielhaus’ repertoire, this record will remain; its importance should not be underestimated.

Lapping up the performance Act by Act and with only the DVD to consider, I sincerely hoped that my personal bias and jaundiced eye didn’t prevent my seeing any hint of beauty or wit. There were some promising moments captured, but these were sadly elusive. A commendable decision by the Director was to appoint Christian Thielemann as her Music Director. The music, the orchestra and the singing kept my spirit afloat.

On the technical problems associated with video productions, I can speak with some assurance, having directed and edited a number of live musical performances—often on location, using a multi-camera set- up linked to corresponding monitors; literally “calling the shots.” Careful preparation and attending the rehearsals with the crew gives one the structure needed to plan the operation, with the cameramen taking instructions by linked headphones, being alerted to prepare for a change in position or angle. Editing live is an adrenalin-charged exercise and success depends on team work and trust: it is a very shared experience.

What gave the “Baptism of Fire” documentary such energy and immediacy was the excellent hand-held camera work. Known fondly as “Wobbly Cam”, operators hopefully can add pace and interesting angles as against static fixed camera positions. While not appropriate—or easy—in the Festspielhaus, in the DVD version one frequently needed shots showing audience reaction and involvement. Mind you, pictures of an outraged audience throwing their cushions and handbags at the stage might have added a certain frisson to the proceedings. Only joking-honestly.

Katherina Wagner’s demands on the cast, often requiring them to handle difficult business, awkward positions and almost unmanageable props, would have made taping her production additionally difficult for the Camera Director. In constantly focusing on close ups, usually to the detriment of the general action, he had little choice. A good example of this is in Act 2 where poor little Eva, wearing her simple blue drip dry shift is being graffitied by the dreaded Walter wielding his lethal paintbrush. She had to hold a series of positions for agonizing minutes on end. Fortunately, she didn’t have to sing. What Hans Sachs was doing, I can’t remember. Frequent wide shots of the entire stage would have been useless because of the impenetrable gloom that seemed to dominate this production. A friendly Labrador and/or a white stick might have helped the unfortunate cast.

Unlike the little black dress, I for one will be glad when the new fashionable black, so loved by Designers and Directors alike, is no longer fashionable. We are supposedly dealing with what is laughingly called a Comedy! In all fairness, l imagine this was not the case when seeing the production in the Festspielhaus. I have to confess that the scene with the inflatable sex doll, seen in the 2007 documentary tended to disturb my concentration when viewing the entire DVD production; I was never sure when she was likely to literally “pop up”. Mercifully, this Plastic Floozy had either exploded or been pensioned off for the 2008 production. The scene that replaced it is, predictably, equally repugnant.

Gloom-laden, the Act I set resembled the exercise yard of a less than salubrious prison. The glum chorus, drilled into submission, when not marching in single file, spent their time building tables. Wearing strange grey wigs and stranger short pants, they resembled inmates from a Dickensian Reformatory, seconded for the occasion. Set in the present day, with the cast in modern dress, made identifying the different characters rather confusing; and the gloom didn’t help. Hans Sachs—chain smoking and shoeless was a delightful idea—a gentle comment on the Cobbler’s profession. Also, the ceiling frescos and duelling jigsaw puzzles were a sensitive reminder of the Opera’s genesis.

Walter was another matter; with obvious “street cred”, he, a Graffiti Artist, looked like someone to be avoided at any cost. Armed with a bucket of paint and lethal paintbrush, he daubed anything or anyone who stood still long enough to express his desperate need to be creative. No surface escaped his attention, including a cello. Eva and Magdalena looked sadly less than chic or remotely desirable, dressed as they were in a style best described as early Schindler’s List. Targeting Eva, her appearance only encouraged Walter’s ardour; he also sang.

The tables, once built and placed together to form one huge rostrum, gave the now manic Walter yet another tempting surface, a new blank canvas, to express his dubious talent. Paint splattered, the Boardroom meeting ended with the grey Reformatory Inmates clearing up the mess. With all the business suits, Beckmesser and David were often lost in the crowd. Hans was always easy to spot—the only one on stage not wearing shoes. But it was the glorious music and equally lovely singing that enabled easier identification.

The Act 2 setting—the “genial summer evening” with the Elder and Linden trees sadly missing and the stage predictably gloomy—had all the charm and comfort one enjoys astride a milk crate on the pavement outside Bar Coluzzi on a wet afternoon. Hans was there, his typewriter at the ready. David was busy doing something, but I m not sure what. A huge hand dominated the stage, but its importance escaped me; then it fell down, which was probably meaningful. This did however provide an elevated position for Walther to graffiti Eva, now wearing her simple blue drip dry dress. She had to hold artistic poses for agonising minutes on end, while Walter, wielding his dripping paint brush expressed himself yet again.

Instead of Manna from heaven, a deluge of Dunlop shoes rained down; multi-coloured, they certainly added welcome colour and movement to the scene. A lute-less Beckmesser was accompanied in his wonderfully grotesque serenade by Hans tapping away on his typewriter. A highlight of this Act was the beautifully choreographed and performed riot scene. That was until the Andy Warhol moment. Another deluge. This time, suspiciously coloured Campbell’s Soup poured down on the hapless cast. I interpreted this to be a condemnation of American Popular Art and its debilitating influence on the cultural world. I got the message, I think. It took the hour interval and an army of resolute cleaners to wipe up the mess.

Act 3 was equally puzzling, with Hans’ simple workshop now resembling the Waiting Lounge of a cut-price airline. Walter, now trying his hand at stage design with predictably little success, spent an inordinate amount of time cutting up cardboard and endlessly toying with his model stage. Constantly wandering in search for excitement, he also had fun with a large soup can. By now, Hans was wearing shoes. Neither dripped, nor dried, Eva was still to be seen in her favourite Blue Dress from the day before. She also wore sandshoes—one red, the other, green which, while showing originality, revealed that she was colour blind and lacking a certain fashion sense.

During the usually lovely and touching shoe fitting scene, Eva had to endure very inappropriate touching by an ardent Hans. I feared the worst. It’s not easy fitting sandshoes; one can easily get carried away. The sly Beckmesser, opera’s favourite pedant and ever the deluded optimist, lurked with admirable stealth.

The scene in the emotionally charged, almost claustrophobic, confines of Sach’s workshop ended with the glorious quintet. This wonderful moment was beautiful realised. Large gold picture frames lowered, left and right, to frame family portraits; a prophetic glimpse of the future awaiting our now married couples, their respective children sharing the moment with doting parents. The pleasure generated by this touching scene was soon shattered when Magdalena’s young son showed the telltale sign of an unfortunate bladder condition. That brought us down with a thud.

Anticipation of the always spectacular scene change to the open meadow—the breath of fresh air, sunlight, the sheer exuberance, and proud dignity of the Guilds—makes this one of the great moments in all opera. Tinged with a little sadness, knowing this delight will soon come to an end, a ripple of excitement envelopes the audience. We become active participants sharing the joy—personally involved. So what did we see? A disappointingly dark stage and a row of dead composers with big heads thinking they were the New York Rockettes. The suitably morose chorus, jam- packed into stadium-style seating which slowly rose up from the Stage floor. Technically very impressive; the result was less than joyous. Eva had at last changed her dress, which was a decided plus—things were looking up! The doll-like dancing girls that so excited David’s interest also had big heads and made one wonder what his problem was. I couldn’t find Magdalena; Hans was wearing shoes for the occasion.

To my relief, the scene where previously the desperate Beckmesser has a dalliance with our accommodating Plastic Floozy, the inflatable sex doll, didn’t eventuate. Whether she exploded, was punctured or simply past her “use by” date, one hardly cared. The scene that replaced these former high jinks was equally turgid and gave new meaning to the word gratuitous. Beckmesser, still lute-less, as well as clueless, rendered his tortured offering to the contest audience. A large surgical trolley was wheeled on stage, piled high with what looked like potting mix. After some time, an excrement-smeared gentleman emerged alive and well—and totally naked. He proudly revealed all, first to the audience then turned around to the now more animated chorus. With that, he walked off, followed by the trolley. Sandshoes might have helped. As if Beckmesser’s song isn’t enough, at this point I gave up, no longer caring who won who or what. In trying to fathom the meaning behind this concept, I thought it best left to Sigmund Freud. Taking my brick-bat, I went home.

Still happily Outraged of Elizabeth Bay.