Wagner’s Jews: A Fascinating Perspective on Wagner’s Attitude to the Jews

By Jim Pritchard

Wagner’s Complicated Relationship with the Jews, now on Film

By Judy Maltz

Richard Wagner was a great composer - but also a virulent anti-Semite

By Adrian Mourbyasks

German opera festival confronts Wagner anti-Semitism head-on

By Pauline Curtet and Deborah Cole

POSTSCRIPT - The Family makes amends

Wagner’s Jews: A Fascinating Perspective on Wagner’s Attitude to the Jews

By Jim Pritchard

from seenandheard-international.com 14/10/2013

It is worth beginning my comments with the publicity blurb for this important new documentary –

The German opera composer Richard Wagner was notoriously anti-Semitic, and his writings on the Jews were later embraced by Hitler and the Nazis. But there is another, lesser-known side to this story. For years, many of Wagner’s closest associates were Jews - young musicians who became personally devoted to him, and provided crucial help to his work and career. They included the teenaged piano prodigy Carl Tausig; Hermann Levi, a rabbi’s son who conducted the première of Wagner’s Parsifal; Angelo Neumann, who produced Wagner’s works throughout Europe; and Joseph Rubinstein, a pianist who lived with the Wagner family for years and committed suicide when Wagner died. Even as Wagner called for the elimination of the Jews from German life, many of his most active supporters were Jewish - as Wagner himself noted with surprise.

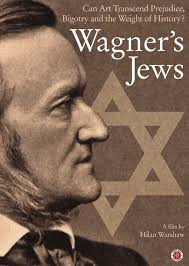

Who were they? What brought them to Wagner, and what brought him to them? These questions are at the heart of Hilan Warshaw’s documentary Wagner’s Jews, the first film to focus on Wagner’s complex personal relationships with Jews. Filmed on location in Germany, Switzerland, and Italy, Wagner’s Jews tells these remarkable stories through archival sources, visual re-enactments, interviews, and performances of original musical works by Wagner’s Jewish colleagues - the first such performances on film.

Parallel to the historical narrative, the film explores the ongoing controversy over performing Wagner’s music in Israel. In a different form, the questions dividing Wagner’s Jewish acquaintances still resonate today: is it possible to separate artworks from the hatreds of their creator? Can art transcend prejudice and bigotry, and the weight of history?

I have never had a problem discussing this issue because although I am not Jewish my mother and grandmother were and they had escaped the Anschluss from Vienna to arrive in England before the Second World War. On film Warshaw, who is a violinist and conductor, never takes sides and pieces together the contributions of his talking heads with consummate skill to attempt to reconcile the ambivalence people might have towards Wagner because of his Das Judenthum in der Musik publication.

I came across a Haaretz interview recently with Irad Atir who recently completed a PhD on Wagner: he suggests Wagner was a special kind of anti-Semite as ‘His opposition to Jewishness was part of his opposition to the socio-political and cultural reality of the period in general, including the non-Jewish German reality. He criticized certain aspects of Germanism; for example, the conservatism, religiosity, pride in aristocratic origins, and militarism. He also criticized Jewish separatism and lust for money. For him, there were good Germans and bad Germans, good Jews and bad Jews.’ Atir, another musician, is reported as believing the only way to understand Wagner’s art, which expresses political, sociological and musicological ideology, is to approach it neutrally. The usual link between Wagner, racism, anti-Semitism and Hitlerism should be ignored – and this, I suspect, is Warshaw’s thesis too.

Atir’s research also sheds light on Wagner’s approach to Jews in his operas and shows it is not as ‘one-dimensional’ as some would want us to accept as fact and that although the composer ‘points out and alludes to Jewish characters; for example, through text that contains sibilant consonants in the case of Alberich and his brother Mime in the Ring, the most important example of a positive attitude, or at least a complex one, is taken from the Ring. The character who must be understood as Jewish – I explain why it must be so through musical analysis as well – is the character Loge, the god of fire. He is cunning but also acts in a positive way, helping good people; a Jew who has undergone change. The music associates him with the German world and the Jewish world. Sometimes it’s gratingly chromatic compared to the accepted mid-nineteenth century taste, and sometimes it’s different, expressing purity.’ Arid continues, ‘Another example: the Rhinemaidens mock Alberich, an ugly “Jewish” character, although he committed no crime against them. The “dark” world within Alberich turns to evil only after the “good” world has hurt him without cause. That means the “good” world also contains elements of evil.’

These thoughts are very much in the spirit of Warshaw’s film though its 55-minutes length does not allow him to explore any of the ideas – pro or contra Wagner – in any great depth.

Who knew there was an Israel Wagner Society? Wagner’s Jews begins with the plans of its founder, Jonathan Livny, to organize a Wagner concert at Tel Aviv University that soon apparently incurred the wrath of Uri Hanoch, leader of the Holocaust Survivors and was subsequently cancelled. Indeed in the film Hanoch is shown saying ‘As long as I live, I will make sure that Wagner will not be performed in Israel.’ If I recall correctly, this was pronounced with the romantic music that accompanies the wedding ceremony at the opening of Lohengrin Act III in the background! Intriguingly Leon Botstein, Conductor Laureate of the Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra, posited that Lohengrin is possibly a classic Jewish fantasy: ‘I – without having my name or my race known – am going to rescue this country. That is the fantasy of the outsider coming into the centre, in triumph. And that’s the fantasy ofLohengrin. It appealed to every aspiring young Jew.’

Following the first screening of the film screening there was a Q&A involving Warshaw, Alan Miller (a film director and co- founder of Truman Brewery) and Igor Toronyi-Lalic (co-founder and classical music editor of theartsdesk.com). It was chaired with all the gravitas of a public school debating society event by someone from the ‘Battle of Ideas 2013’ and really didn’t reach much conclusion. Miller thankfully seems to disagree with Woody Allen’s quip that ‘Every time I hear Wagner I feel like invading Poland’ and Toronyi-Lalic dug himself into a hole with some nonsense about Wagner as misanthropic and anti-humanist and showed little of the open mind needed, I would have thought, for a ‘classical music editor’. Peculiarly he suggested he was repulsed by Wagner yet embraces his music – in another context this is the argument some of those trapped by Operation Yewtree try and get away with!

I believe Warshaw got closest to the truth about Wagner suggesting that he was just trying to create a stir with Das Judenthum in der Musik and he gives evidence for this in his film. I agree it undoubtedly reflected some of Wagner’s despicable private opinions but it is clear that there were nuances to his anti-Semitism that allowed him to befriend Jews and I will never accept it was just that he had to exploit them for his own ends. Put simply – in the days before social media – he needed to court controversy to get himself better known.

For more about Wagner’s Jews visit http://www.overtonefilms. com/wagners.html.

Wagner’s Complicated Relationship with the Jews, now on Film

Judy Maltz www.haaretz.com May 15, 2014 9:32 AM

New York musician Hilan Warshaw found himself smitten by Richard Wagner in his youth, and set out to understand his ‘push-pull’ relationship with Hitler’s favourite composer.

The music of German composer Richard Wagner was never played in his parent’s home: Too many bad associations with Hitler and the Nazis, explains filmmaker Hilan Warshaw.

So it wasn’t until he began playing violin in a New York City youth orchestra that Warshaw was first introduced to the work of the notoriously anti-Semitic 19th-century German opera composer. And rather embarrassingly, he found himself smitten. I just loved the music. But, at the same time, it was something that my conscious mind told me was anathema, he recalls.

Over the years, Warshaw – whose family lost many relatives during the Holocaust – developed what he describes as a push-pull relationship with Hitler’s favourite composer. And it made him curious about the other Jews in Wagner’s life. So curious, in fact, that he decided to devote the past several years to making a film on the subject. The fruit of that effort, Wagner’s Jews, is playing in Tel Aviv at the Docaviv festival, Israel’s premier event for documentary film.

Produced, directed and written by Warshaw, the feature-length film focuses on the Jews who were some of Wagner’s closest associates, among them the gifted young pianist Carl Tausig, who was almost like a son to him; the conductor Hermann Levi, who happened to be the son of a rabbi; and the pianist Joseph Rubinstein, who lived in Wagner’s home for many years and killed himself when the composer died.

The film also explores the complicated relationship of post- Holocaust Jews, both in Israel and abroad, with Wagner’s music. Although it is not well known that Wagner had many Jewish supporters and friends, notes Warshaw, neither should it be all that surprising. Wagner was not living in 1938 Germany, he notes. He was living in the mid-to-late 19th century, and it would not have been possible for him to operate effectively in the music world of his time without coming into contact with Jews, since there were many in the music world in Europe at that time.

“It’s also not surprising that these Jews were willing to be associated with him, because if they were not going to associate with every composer who expressed anti-Semitism, the only ones left for them to be working with would be their dads.

Wagner’s anti-Semitism was certainly not a rarity at the time, but neither was it as prevalent as assumed, according to Warshaw. His case in point is the little-known story, brought to light in the film, of Wagner’s first wife, Minna Planer. Although they had a rocky relationship from the start, it was Judaism in Music – his famous essay attacking the Jews – that brought things to a head in their marriage. This proves there was a virulence to his anti-Semitism that even his wife couldn’t deal with, posits Warshaw.

The son of an Israeli mother and American father, Warshaw grew up in Manhattan, where he attended Ramaz yeshiva high school. As for his unusual name: I tell people it’s a new- age Hebrew name – a masculine form of Hila. He studied conducting at the Mannes College of Music in New York and Aspen Music School, before transitioning to film studies at New York University.

The reason I left conducting is that I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life interpreting someone else’s work – I wanted to create my own, he says. It was also a natural move because for me; film is very, very musical. And by making films about musical subjects, my love of music stays alive.

Did Warshaw’s work on the film change his views? Originally, when I heard that Wagner had many Jewish associates, I thought that maybe he was just an anti-Semite in theory but not in practice, or that maybe this is something not as extreme as we’ve been led to believe, he responds.

But while working on the film, my view of Wagner the man became darker, because the more I explored his relationships with Jews, the clearer it became to me that these were largely exploitative relationships.

When asked if he supports or opposes the ban on staging Wagner’s operas in Israel, Warshaw hesitates for a moment. I don’t have a strong moral feeling about this one way or the other, he says. Let me put it this way. I can understand the reasons for the ban very well. But I actually think that people make a bigger deal of it than needs to be made, because Israel is not the only example in the world of a democracy where performing arts organizations tailor their repertoires to what they think their audiences will accept.”

“I don’t think it’s a freedom of speech issue – I think it’s an issue of a social symbol,” he added. “So I understand the ban and, to a certain degree, I really empathize with it. But I can’t really say I’m 100 percent in favour of it, the reason being my own life experience. “I grew up in America, not in Israel. I had the opportunity to play Wagner’s music, to study it, and those were formative experiences for me. I‘m aware that had I grown up in Israel, I would probably not have been able to have those experiences. So for me to come out and be a partisan of the ban wouldn’t be 100 percent honest.

Richard Wagner was a great composer - but also a virulent anti-Semite.

As the Wagner festival at Bayreuth opens, Adrian Mourbyasks whether we can play his music with a clear conscience

theguardian.com/au Friday 21 July 2000

Around 150 years ago, a failed composer and revolutionary used an assumed name to publish his latest 25-page pamphlet. Although Richard Wagner’s ideas were to find their final form 20 years later in his opera cycle The

Ring, his early attempts at philosophy reflect recognisably Wagnerian concerns: that nature is destroyed by industry; that it is unnatural to pursue power at the expense of love; that capitalism is corrupt; that the state often at odds with the people; that we live in an age where entertainment is considered more important than art.

Nothing much to argue with there. But what people today remember from Wagner’s quasi-philosophical period is his contention that it was the Jews who were responsible for much that was going wrong in art and society. His essay Das Judentum in der Musik (Judaism in Music) contained an attack on one Jewish composer in particular. “Mendelssohn has shown us that a Jew can have the richest abundance of talents and be a man of the broadest culture,” he wrote, “but still be incapable of supplying the profound, heart-seizing, soul-searching experience we expect from art.”

Had Wagner not written Judaism in Music his views on Europe’s Jews might have gone with him to the grave. Certainly we would probably not find his music banned in Israel today, nor a whole academic industry involved in mining his musical texts for seams of anti-Semitism.

The notion that artists don’t have to be as beautiful as the works they create is a commonplace now - except in the case of Wagner. Judaism in Music is what has made him the unforgivable exception. There are many people who would like to see the book banned and who treat the idea of even discussing Wagner’s views as revisionist and inherently racist. Yet, as Alexander Knapp, lecturer in Jewish Music at London University points out, “Wagner was not the only the only composer to show antagonism towards Jews. Chopin, Liszt and Mussorgsky are also on record as having made comments that could be regarded as anti-Semitic.”

Indeed it was a 19th-century commonplace for left-wing revolutionaries - Marx among them - to be hostile to the Jews whom they held responsible for propping up bourgeois capitalism during the failed revolutions of 1848-50.

Why then is Wagner singled out today for such opprobrium? In Knapp’s view, “The crucial difference is that Wagner was espoused by Hitler and the Nazis.” Although Wagner did not advocate the Holocaust - he died before Hitler was born - there is no doubt that his music was adopted by Germany’s architects of mass destruction.

The American academic Paul Lawrence Rose, author of Wagner: Race and Revolution, is a firm believer that Jews must make sure that Wagner is never forgiven. “There was a Holocaust and Wagner’s self-righteous ravings, sublimated

into his music, were one of the most potent elements in creating the mentality that made such an enormity thinkable,” he says. “If time renders ridiculous the ban on Wagner, then the simple passage of time will also cause the Holocaust itself to fade into a distant memory. Appalling as this possibility is it seems likely to eventuate.”

Rose has no truck with either seeking to understand Wagner’s anti- Semitism or separating it off from his musical output. “The only way to counter this abyss of forgetfulness is through ritual or institutional forms of remembrance. The Israeli ban on Wagner is a pre-eminent rite for warding off the dissolution of one of the core experiences of Jewish history and memory.”

In Tel Aviv today, the New Israeli Opera still has no plans to perform Wagner, although the question is hotly debated. There have always been Jewish enthusiasts for Wagner and great Jewish interpreters of his work. Daniel Barenboim and James Levine have both conducted at Bayreuth. Zubin Mehta, musical director of the Israeli Philharmonic, has tried on four occasions to programme Wagner but has always been dissuaded by the force of public anger.

The musical director of New Israeli Opera, Asher Fisch, has made no secret of the fact that he’d like to hear Wagner performed. “What is happening here is Israeli society taking an easy way out,” he says. “We have German cars now, we have German electric machines in our homes. We have regular relations between our governments and armies, but we seek to ban Wagner. Why do we do so? Because there is no money tied up in culturally elite activities like music. No one suffers financially if we refuse to play Wagner or Beethoven. In Israel we only reject Germany where it does not matter.”

But those who seek to exonerate Wagner by differentiating between the composer and the pamphleteer have another problem: the argument that anti-Semitism underpins not only his philosophy, but his music.

Knapp is suspicious of these arguments. “For me music, per se, cannot be anti-Semitic,” he says, “though its context may be - a distasteful parody or racist text for instance. But how can a chord or sequence of chords be anti-Semitic?”

But a fellow Jew, the American academic Marc Weiner, has traced anti-Semitic images through the Wagner canon. “Wagner’s anti-Semitism is integral to an understanding of his mature music dramas,” he says. “I have analysed the corporeal images in his dramatic works against the background of 19th-century racist imagery. By examining such bodily images as the elevated, nasal voice, the ‘foetor judaicus’ (Jewish stench), the hobbling gait, the ashen skin colour, and deviant sexuality associated with Jews in the 19th century, it’s become clear to me that the images of Alberich,

Mime, and Hagen [in the Ring cycle], Beckmesser [in Die Meistersinger], and Klingsor [in Parsifal], were drawn from stock anti-Semitic clichés of Wagner’s time.”

Given that Wagner blamed the Jews for the materialism and reactionary values that were inhibiting Europe’s spiritual development, it was perhaps inevitable that he drew on Jewish clichés to create his villains. Surprisingly, though, Weiner refuses to write off what Wagner does with them. “Wagner’s racism led him to create some of his most complex, rich, and enigmatic dramatic figures, as well as some of his most haunting, iconoclastic, and beautiful music,” he says.

There are of course are those who refuse to accept that Wagner was anti-Semitic at all - but such an argument carries no serious weight today. In the view of John Deathridge, professor of music at King’s College, London, both Wagner’s defenders and detractors are missing the point. “I think the admirers are in denial and the critics overplay the Jewish issue,” he says. “In the end neither position accounts fully for the obviously wide resonance Wagner’s works still enjoy.”

He also points to the new ending that Wagner added to Das Judentum in der Musik when it was republished - this time with his own name on the title page - in 1869. “Wagner actually addresses the Jews, by saying, ‘Remember that one thing alone can redeem you from the curse which weighs upon you: the redemption of Ahasverus - destruction!’ This cannot mean that Wagner is literally calling for the destruction of the Jews, since in the same breath he is offering them redemption. What Wagner is suggesting, in theatrical language, is that Jews should rid themselves of their Judaism. This explains why Wagner offered to take Hermann Levi, the first conductor of Parsifal, and a Jew, to have him baptised

a Christian. Wagner is not advocating murder! He can’t be, otherwise why bother to suggest the idea of redemption?”

There is no doubt that the debate over Wagner’s anti- Semitism is going to rumble on and, as we approach the end of this first decade of the 21st century, the preparations for his 200th anniversary will no doubt be overshadowed by Jews who claim that by celebrating Wagner the world is denying the suffering of their race.

But Weiner believes that it is in his people’s own interest to stop boycotting Wagner. “It would be naïve to feel that we must whitewash Wagner’s works in order to be able to enjoy them, for such an argument suggests that there is such a thing as an ideologically unproblematic work of art. On the other hand, it would be equally indefensible to censor the works (their performance or publication) altogether, even in Israel, for, ironically, to do so would mean that Wagner had won - that his works were indeed reserved for Germans, and that Jews had no place in their reception and enjoyment.”

Whether a 19th-century composer can be forgiven for an act of 20th-century genocide remains to be seen. The argument is bound to rest with the Jews, who are divided between those who accept Wagner with his faults and those who see him as a hate figure: one who must continue to be punished beyond the grave for acts that were not perpetrated in his lifetime.

German opera festival confronts Wagner anti-Semitism head-on

Pauline Curtet and Deborah Cole

www.timesofisrael.com 26 July 2017

Edgy new production by Australian Jewish director met with rapturous applause and rave reviews at renowned Bayreuth festival

BAYREUTH, Germany (AFP) - An edgy new opera production by Australian Jewish director Barrie Kosky tackling Wagner’s anti-Semitism head-on won rapturous applause at Germany’s renowned Bayreuth opera festival and rave reviews Wednesday.

An audience including German Chancellor Angela Merkel cheered the four-and-a-half-hour staging of “The Master- Singers of Nuremberg” on opening night Tuesday at Bayreuth, the festival dedicated to the works of Richard Wagner. Critics said they were impressed with the first production ever by a Jewish director at Bayreuth, now in its 106th year, and called it chillingly relevant.

Spiegel Online said Kosky’s “remarkably entertaining and convincing” staging effectively used Wagner’s notorious anti- Semitism to take on “hatred of Jews in general” in today’s Europe.

National daily Die Welt said Wagner’s toxic ideology had always been an “elephant in the room” which Kosky had opted to make “the actual subject of his staging.”

Wagner’s musical and artistic legacy from the 19th century is infused with anti-Semitism, misogyny and proto-Nazi ideas of racial purity. His grandiose, nationalistic works were later embraced by the Third Reich, and Adolf Hitler called him his favourite composer.

Nevertheless in purely musical terms, Wagner’s achievements are undeniable and his operas figure in the standard repertoire of houses around the world - apart from Israel which maintains an effective ban on public performances of his work.

The Bayreuth festival, still run by the Wagner family, long tried to separate the works from their murky origins. But reviewers said the pairing of Kosky with one of Wagner’s most iconic operas marked a bold break with that tradition.

First performed in Munich in 1868, “The Master-Singers” is essentially a hymn to the supremacy of German art. It was one of Hitler’s most-loved operas and its music was misused for propaganda purposes by the Nazis.

‘Frankenstein creation’

In the production, Kosky embeds the opera’s setting of Nuremberg in the city’s grim 20th century history as the birthplace of the Nazi race laws, the setting of the party’s giant torch-lit rallies and, after the war, the scene for the trials of Hitler’s henchmen.

An entire act is set in the Nuremberg Trials’ wood-panelled courtroom, and a key character, the town clerk Sixtus Beckmesser, is presented as a grotesque Jewish caricature recalling Nazi smear-sheets.

“I am the first Jewish director to stage this piece in Bayreuth and as a Jew that means I can’t say, as many do, that Beckmesser as a character has nothing to do with anti-Semitism,” Kosky told public broadcaster 3sat. “Of course it does. In my opinion Beckmesser is a Frankenstein creation of everything Wagner hated - Jews, the French, the Italians and critics.”

Kosky has run Berlin’s Komische Oper for five years and introduced a little-known repertoire from the turbulent 1920s and 1930s by Jewish composers later forced to flee the Nazis. He admitted in an interview with AFP last year that he has “many contrasting emotions” about Wagner’s masterpiece.

“Can you just portray the work as just being a simple fairy story, (given) the history of the piece?” he asked.

POSTSCRIPT - The Family makes amends

In 2012 Bayreuth inaugurated “Silenced Voices”, an impressive open-air exhibition directly in front of the opera house. This addressed the Wagner family’s involvement with Nazi regime propaganda and its direct effect upon the festivals anti-Jewish casting policies. It showcased twelve large panels portraying the tragic life stories of 53 Jewish artists, musicians and singers associated with the festival who were persecuted, defamed or not employed for “racial” or political reasons. Due to the great response from guests and citizens, the city of Bayreuth decided to keep this installation on the “green hill” permanently.