By Colleen Chesterman

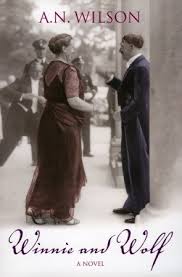

A. N. Wilson’s novel Winnie and Wolf was published in 2007 and having read it in early 2008 I suggested to Terence Watson that it should be reviewed for our newsletter. A sensible man, he suggested I do it – and here at last is my review. I hope that many members of the Society have already read this book; if not I would like to recommend it for an original and lively introduction to the world of the Festspielhaus and the Wagner family.

The Winnie of the title is Winifred Williams, Richard Wagner’s Welsh daughter-in-law. Wolf is the Führer, Adolf Hitler, who shares a close relationship for Winnie and is a regular visitor to Wagners’ home and a genial uncle and friend of the Wagner children. The novel is narrated by Herr N., a Bayreuth local with an interest in philosophy and music who becomes Siegfried Wagner’s assistant. It emerges at the end of the novel that it is in fact a confessional letter to his adopted daughter, a resident of Seattle, who is the illegitimate child of the Hitler-Winifred relationship, although her parentage was not known to Herr N. until many years after the adoption.

In reviews at the time of its release, Wilson’s book was criticised for presenting a human portrait of the Fuhrer and by doing this to minimise the unspeakable nature of his policies. It is a reasonable criticism to make. I would argue that through his narrator, Wilson suggests criticisms of Hitler. Some go no further than making him a figure of fun, vigorously farting while delivering speeches and (Herr N. suspects) while making love, but then Herr N. is in fact consumed with jealousy of Hitler, because he himself is desperately in love with Winnie. Herr N. is explicitly critical of other Nazi leaders: he refers to the club-footed Goebbels as Nosferatu and Göring as the Mad Gamekeeper. The most compelling reason for not seeing the book as a defence of Hitler is the fact that the only scenes that burn with emotion involve Herr N.’s principled family and their opposition to Nazism. His father, a Lutheran minister, links arms with Jews and non-Jews to protect a Bayreuth synagogue on Kristallnacht. His brother Heinrich is given a savage beating by Nazis and later hanged.

For those of us interested in Wagner, however, the pleasure of the book lies in its detailed picture of the cultural milieu of Bayreuth and the Festspielhaus. Wilson is clearly passionate about Wagner and his music and the book is full of detail – it is more a cultural biography of the history of the Festspielhaus and the people involved than a novel. This is a complex book, operating on many levels. It covers a number of periods as Wilson moves between Wagner’s life, the Weimar Republic, the philosophies that interested Wagner, the struggle to establish the Bayreuth festival, the activities of Wagner’s extended family and the horrors of the Second World War.

The novel is in sections named after Wagner’s operas, and follows them in a loosely chronological pattern, though for reasons to do with the development and timing of the story Parsifal and Tristan und Isolde are followed by Gotterdammerung, in which the Allied bombs rain on Bayreuth and all except Winnie are aware of the destruction directed at the Nazi administratio. Within each section there are passages following Richard Wagner’s development as a composer together with sketches of his personal life. Wilson discusses for example how Tristan und Isolde relates to Wagner’s love for Mathilde Wesendonck. He also involves Wagner’s absorption of philosophical theories and religious beliefs. We get a vivid picture of Wagner as a theatre composer who loves working with “overwrought, egoistic, highly sexed thespians.” Interestingly Wilson also emphasises Wagner’s obsession with detail, even in the midst of his creation of a metaworld of myth.

These pictures of the past, which includes the planning and construction of the Festspielhaus, are mixed with contemporary stories dealing with Herr N.’s work for Siegfried Wagner, or Fidi. There is a clever portrait of the elderly Cosima Wagner. There is also much lively gossip. Fidi is a kindly and entertaining figure and also riotously gay, endlessly pursuing chorus boys. Toscanini is temperamental and so demanding that the musicians called him Toscanono. Tietjens is portrayed as able to ignore all that is happening around him as he focuses on details of music and character, in particular in his development of a production of Parsifal

In the centre whirls the determined figure of Winnie, ensuring that Bayreuth is developed and maintained and wheedling all around her to support this with money or special treatment. Hitler caves in to Winnie’s demands. She knows that Jews and homosexuals, both victimised by the Nazis, helped create Bayreuth: “Half the chorus are pansies and one-quarter of the orchestra is Jewish.” Despite her public anti-Semitism Winnie ensures that the Jewish musicians she needs at Bayreuth are left alone. The Bayreuth Festival, suggests Wilson, remained the one area of artistic freedom in all of Germany.

In the complex structure of the book Wilson (in the person of Herr N.) reflects on the characteristics of Wagnerian opera that could have attracted Hitler. Herr N. ponders on Wagner’s late work, which he suggests provided for the Nazi leader a pre-Enlightenment “Gothic depth of the irrational”, “a fertile, poisonous soil of mythology”. But these were what Hitler wanted, not what Wagner had provided within his glorious sound. Herr N. is clear that Wagner should not bear blame for later vicious policies. Winnie and Wolf is not a perfect book, but it is fascinating in its depiction of Wagner, his intellectual, musical and personal development, the phenomenon that is Bayreuth and how it survived the turbulent period of the Nazi hegemony.