Joseph Ferfoglia, Member no. 45

By Roger Cruickshank, Member no. 669

In Memoriam: Joseph Ferfoglia

I heard third-hand, a few months ago, that Joseph Ferfoglia had died. I met Joseph and his second wife, Judy, through the Wagner Society, and we became good friends in a period late in their lives, before the slow descent into old age shut them off from the world. I thought I should gather together some of the fragments I recall of Joseph (and Judy), in a vaguely chronological order, so that they weren’t lost, at least for a little while.

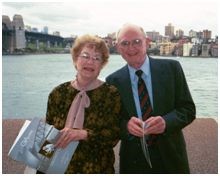

Judy and Joseph at the Opera house for the farewell concert

for Maestro Cillario, on 23 March 2003

Joseph was born on 31 March, around 1923 (as best I can work out), in Trieste, a heritage of which he was intensely proud. Trieste was the Mediterranean port for the Austro-Hungarian empire, and during the Great War, Joseph’s father had been a driver for the German imperial army; a photo of his liveried father standing next to an extraordinary motor vehicle hung on their wall. Between wars, the family ran a delicatessen, and from an early age Joseph enjoyed the best of food from his region.

As Joseph told it, when the German army occupied Trieste in WW2, they assumed its people would be natural allies, but their fierce nationalism outweighed their Austro-Hungarian heritage. Joseph was caught up in anti-German activity, captured, and sentenced to be deported to a labour camp. Joseph was being escorted across the great marble concourse of the Trieste railway station by a young German soldier. Both were 18, and they talked to each other in German. Suddenly, the soldier looked at Joseph and said “Run!” and Joseph did, not looking back, not knowing if he would be shot while escaping, far into the hills and mountains surrounding Trieste, where he remained in hiding until the end of the war. When he returned home, Joseph found that many members of his family had been deported and died in labour camps, mainly from starvation in the closing days of the war.

Trieste had an opera house perhaps second in importance to La Scala in that part of the world, and when he joined the payroll section of the Trieste police, Joseph was able to attend concerts and operas almost every night, resplendent in his dress uniform, and to experience first-hand what he came to see as the close of a golden age of European music and culture. Trieste was now under the control of Italy, which Joseph saw as a betrayal, a perverse reward to Italy for siding with Hitler.

He decided to leave, and around 1955 boarded a boat for Sydney where he found work as an accountant. According to the Wagner Society’s membership records, Joseph and Judy joined on 20 March 1981, Members number 45. After he retired, he and Judy built a home in Leura, incorporating green building techniques which were almost unknown at the time, such as passive solar heating from a large concrete slab extending well beyond the northern side of the house, which helped conduct heat to warm the marble floors in every room. He had brought a little Trieste to Leura.

Like many Society members, he and Judy met and became friends with the dynamic Olive Coonan, and Joseph audited the accounts in the 90s while she was treasurer. Olive would stay in their Leura home and look after it while they were holidaying overseas, and she nominated Joseph as an honorary life member of the Society, in recognition of his many services. He was devastated when Olive was found to have committed a substantial fraud over many years while in various positions in the Society, and realised that the records he had audited had all been forgeries. He never fully recovered from her betrayal of his trust and friendship.

Around this difficult time we became close friends, and I enjoyed Judy and Joseph’s generous hospitality over many weekends in Leura. Joseph was an avid and excellent photographer, and Judy a careful diarist, and I enjoyed many happy slide evenings with them, as they showed the pictures of their European trips, including to Trieste, Cremona, and the Dolomites, all meticulously catalogued and beautifully presented. The secret to a peaceful slide evening was to control the slide advance mechanism, and to moderate the occasional disputes when the memory of the photographer and the evidence of the diarist differed.

Whenever I visited, we took long walks in the bush, or through the streets of Leura. As Joseph’s hearing diminished, he found that the best way to communicate was to stand directly in front of you and watch your lips carefully, which made telephone calls a waste of time, and frequently brought our walks to a halt. I think he had a hearing aid, but preferred not to use it. Stubbornness was another of his virtues.

Joseph found modern opera productions generally not to his taste, and was forthright in his views. He also thought that there was a decline in the standard of opera singing at the highest level, and often recalled the singers he had heard at the Trieste opera. Joseph and the Argentinian conductor Carlo Felice Cillario met in Australia, became friends, and corresponded until Cillario’s death in 2007. According to Joseph, Cillario shared many of his views on the standards of signing and productions.

When Judy and Joseph realised that their health no longer allowed them to live comfortably without care, they moved to a retirement village in Waitara, where I last visited them in 2006. As their health declined, they postponed visits until they were able to make lunch and once again offer their warm and generous hospitality. Those days, sadly, never returned.

Joseph had a son by his first wife. His son married and left Sydney, after which he had no contact with his father. Over 30 years later, now living alone on the Central Coast and dying of cancer, Joseph’s son asked mutual friends to contact his father and they were reunited; Joseph was able to visit him daily until his son passed away.

Joseph possessed the best values and traditions of a European. He was warm, generous and passionate in his friendships and his life, and in his love of music and Wagner; he shared these passions with anyone who would listen. Leaving behind the events and the aftermath of the war, he created a new life enriching his new country with the values and culture of the old. He passed away in his 90th year, and is survived by his wife, Judy, whom I’m told has now moved to a retirement home back in the Blue Mountains. His was a hard life honourably lived, and I am proud that, for some of that life, he called me his friend.

Roger Cruickshank, Member No. 669

Past President

Honorary Life Member