By Roger Cruikshank

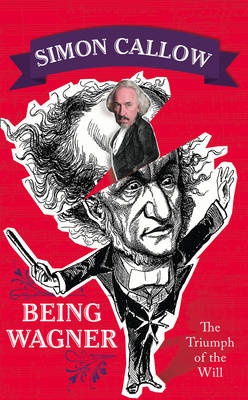

There’s a lot to recommend in this book, the most recent addition to the shelf of Wagner biographies. It’s a good story well told, and worth your time reading. In the unlikely event that you’ve resisted the urge to tackle a biography of Richard Wagner, or that you’re interested in brushing up on your knowledge, “Being Wagner” is well worth the read. But get it from your local Library. Its author, Mr Simon Callow, is perhaps best known in the antipodes as an Actor and the Narrator of TV programmes on classical music and travel. But he’s also a well-regarded writer of biographies, including three volumes on Orson Wells, two on Dickens, one on Charles Laughton, and a recently revised autobiography “Being an Actor”. Now there’s “Being Wagner”.

The first challenge for many readers to overcome will be a prejudice against Mr Callow the Actor, so that they can find the special voice that Mr Callow the Biographer brings to his telling of Wagner’s life story. Mr Callow is not the pre-eminent English gay Wagner-loving public intellectual. That honour goes to the comedian, actor, author of fiction, television personality and self-confessed Wagnerian, Stephen Fry. Who hasn’t seen his self-indulgent DVD “Wagner and Me”, with the cringe-making “pinch me, pinch me” moment when seated at Wagner’s piano in Wahnfried? Or seen Mr Fry in the Bayreuth car park encountering Katarina Wagner? But it would be a mistake to think that Mr Callow is in any way less of a writer than Mr Fry, simply because we don’t immediately recognise him as such. (And yes, this reviewer will one day overcome his infantile prejudice against Mr Fry. Just not yet.)

According to Mr Callow, the impetus for writing this biography came after a one-man stage show he was asked to create for the 2013 Wagner bicentenary, which Callow called “Inside Wagner’s Head”. Starting with four and a half hours of material, he whittled it down to a manageable size for a one-man show but threw nothing away. This mass of material was the start of his book. Words are the tools of Mr Callow’s trade, and he loves playing with them. His book is not that of an academic or musicologist, and his language is very 21st century, which makes it easy to read, and often delightful. Some might call his style “breezy”. Even so, he occasionally sent me in search of my dusty old two-volume Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on Hysterical Principles, as when he describes Wagner as a “diminutive and often rebarbative man” who, when in pursuit of his goal, was “titanic, demiurgic, superhuman, and ... more than a little alarming.” In case you need to know, “demiurgic” refers to a Maker of the world in Platonic philosophy, and “rebarbative” means unattractive or repellent, and isn’t a nice thing to say about someone.

Mr Callow’s love of words often gets the better of him, as for example when he takes flight, describing Meistersinger as “that cornucopious work, which is everything Wagner said an opera shouldn’t be – brimming with tunes, arias, duets, ensembles, counterpoint, a huge chorus, spectacular public scenes, jokes, hijinks – recognizable human beings... Where was all that lurking inside the difficult, rebarbative, violently prejudiced, myth-forging, subconscious-probing, serially betraying, Schopenhauer-gorging, Feuerbach-chomping pessimist with his tragic view of life?” Where indeed, dear reader. Then there are turns of phrase whose very Englishness charmed me. Mr Callow tells us that being pursued by brass bands playing his overtures might have been flattering for Wagner, but it “buttered no parsnips”, meaning that it didn’t help pay the bills. As an aside, Mr and Mrs Google claim that, before the ubiquitous potato reached England from the Americas in the 1580s, the now-despised parsnip was the main carb of the Kingdom. People often wonder about Italian food before the tomato, but seldom about English Cuisine (which some say is an oxymoron) before the Chip Butty. But I digress.

What unique view does Mr Callow bring to a biography of someone whose life and writings have already been disinterred with such forensic thoroughness? He gives us his perspective as an actor and writer, for whom the text precedes everything. Wagner’s poems (a.k.a. the libretti) are the start of each composition, and to Wagner as important as the music. The writing of each poem, and then its reading to a select group, was a ritual after which the composition of the music followed. I’ve heard lovers of Wagner’s music say that, had they been invited to such a reading, they would have declined, preferring to stay at home and rearrange their fridge magnets. But in “Being Wagner”, Callow gives a real sense of the way in which the poems and readings were as vital a part of the creative process as the music itself, a view which is gaining some currency with the recent performances of some of Wagner’s poems as plays in their own right, without any music.

All this is the silver lining that this biography brings. Facts, whatever they may be, are the bread and butter of a biography. No-one writing about Wagner today is likely to un-earth new material, and speculation on the contents of the 70-odd letters which Cosima destroyed after Wagner’s death won’t make them re-appear. His is a life that has been minutely examined, and what makes a biography for me is the “spin” the author chooses to put on the material they include, and just as important, the material they choose to discard.

I’ve always been very fond of Wagner’s Flight from Riga and his Debts, a tale often embellished to Biblical Proportions, which can include a dangerous crossing of the border on foot by night, the overturning of their ‘stage coach’ and Minna’s miscarriage, the journey to Paris by boat rather than overland as they had planned, the monster storm which drove them to seek shelter for days, the songs of the sailors echoing around the cliffs, Wagner’s dog taking charge of the alcohol, their arrival in London on the way to Paris, and much more. Sadly, Mr Callow chooses to relegate this to only a few words.

This Flight, as recounted in Wagner’s autobiography Mein Leben (“My Life”), reads like the Indiana Jones script of its time. But Mein Leben is notoriously unreliable, having been written at the request of Wagner’s dear friend and platinum donor, King Ludwig II. It’s often assumed that Wagner omitted any stories of his marital infidelities because he was dictating the work to Cosima Liszt, who became his second wife, although when they began this great undertaking she was Cosima von Bulow, with whom he was living in sin until their wedding in August 1870. I think it’s far more likely that this curious mix of fiction and memory which they created together omitted this and anything else which might have distressed their Great Benefactor. It provides a sanitized poem of Wagner’s life creating the memory he wanted to leave to the world. I also suspect that while the book Mein Leben is owned by many Wagnerites, it has been read to the last page by very few. Like the more popular Richard Hawking’s “A Brief History of Time”.

Mr Callow relies heavily on Mein Leben for the story of Wagner’s years up to 1864. As I’ve mentioned before, one result of Mr Callow’s re-telling Wagner’s life as told in Mein Leben is that you can hear it in a 21st century voice, which is refreshing. If there was a modern English translation of Wagner’s life novel for his bi-centenary in 2013 it passed me by, and we still have the quaint early 20th century translation speaking to us across the ages. But without Wagner’s own words to guide him, Mr Callow’s writing about the years post 1864 becomes a little dryer, and in places (is this possible?) a little boring. He dutifully covers all the controversial issues, such as Wagner’s anti-semitism, but has little new to say.

And that hints at the misty cloud hanging around this biography. Why was it written at all? Do we finish reading it with any insight into what it was like, “being Wagner”? I don’t think so. Is it more than just a telling of facts, an analysis which allows us to learn about a genius, without ever inhabiting him? Yes, Wagner was driven, and his output was a triumph of his will, but that seems incidental to the sweep of his life and times as told here.

The book has provoked many reactions, often in surprising places. For example, there was a passing slight in a review of the re-released full four-and-a-half hour version of the early 70s movie Ludwig by Luchino Visconti in The Wagner Journal (Vol 13 No 1, March 2019). The reviewer, a Mr Horowitz, reflected that “Visconti rejects the cartoon cad some made Wagner out to be (and still do – see Simon Callow’s recent hatchet job, Being Wagner).” Two feelings engulfed me; mild outrage in defence of Mr Callow’s book, and remorse, since I had promised Mike Day a review of that book and had failed miserably to produce anything. This, dear reader, remedies that second feeling.

I confess that I only read “Being Wagner, etc” three times, so something as subtle as a hatchet job could well have passed me by unremarked. The first reading was that bold venture one makes into a new book, starting at the beginning and finishing at the end. That’s not something I always achieve with books. The second reading was with paper and pen in hand, to record things which might need to be accurately quoted in a review; and the third was an accident, when I took the book with me on a domestic holiday and, staying with literate friends whose library contained much of interest, chose instead to read this in the manner of a “bodice ripper”, which alas it isn’t. But “hatchet job”? I missed that.

And if I can question why Mr Callow wrote his book, you can surely ask why I am writing this review, other than to keep a promise made to Your Editor almost three years ago? (With any luck, the book will have been remaindered by now, and be out of print.) In the day, I was an opinionated bigot on the matter of opera, and Herr Wagner’s place in it. While in my dotage I try to sound calmer and more balanced, I still am. If you asked me what my favourite opera was, I’d tell you it was Madama Butterfly, or Don Giovanni. That’s because it doesn’t make sense to me to speak of Wagner favourites, in the way that parents have a favourite child. Just one of his ten mature works cannot come first; they must all come first (yes, even alas, Meistersinger).

Would I recommend a different book to you? Yes. From left field, Sue Prideaux’s biography “I am Dynamite! A Life of Friedrich Nietzsche.” Among other things, it talks about the Wagner – Nietzsche relationship from Nietzsche’s point of view, and of his intimate relationship with Cosima, often neglected in biographies of Wagner.

Thomas Laqueur, in his review of Being Wagner in The Guardian (10 June 2017) writes, as an aside to a comment on the appropriation of Wagner’s music by totalitarians, of Siegfried’s funeral music in Götterdämmerung: “It wasn’t just the Nazis who appropriated this music for ritual purposes. A brass band of 500 played it to accompany a cannon salute at Lenin’s funeral. A real orchestra played it again at the Bolshoi.” Don’t you wish you’d been there? And don’t you wish that this reviewer was better read and had interesting snippets like that to drop into his review. I do.

1 March 2020