By Minnie Biggs

I saw the last two performances at the Met conducted by Asher Fisch, and the High Definition film at the Dendy cinema, really just to hear Simon Rattle in the pit. It was wonderful to be back in the Met, after more than 25 years, seeing the people, the glamour, the house, those chandeliers rising up before the start, breathtaking. And on the back of the seat in front of me were subtitles/surtitles, in both English and German. I chose to look at the German, when I looked, just to have the words together with what was being sung. It was said that they were funded by a famous crook, now in jail! A rich crook. And speaking of rich, a glass of champagne costs $20 and is served in pretty plastic glasses, which I fear are not recycled.

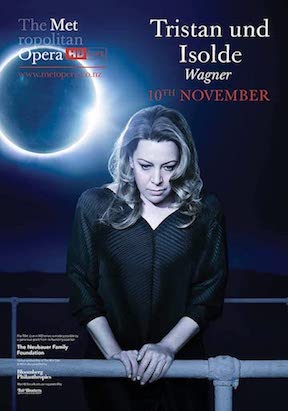

Too much has been said about the dark production byTreliński, filled with non sequiturs, and with little relation to the story or the music, and never about the fact that all the critics and commentators described the opening projection as a huge nautical compass, when it is in fact a radar screen, not a compass, which, like much else, bears no relation to the opera.

The Met orchestra is beyond compare, all agree, and with Simon Rattle at the lead, better than best. Something about a super maestro at the head of a super orchestra producing superb music. He had studied the score that Mahler had used, and said that balance and transparency, allowing the instruments to play out to beyond the end, was an important aspect he absorbed.

It is impossible to compare the sound of the live performance with the film but there is no question that Asher Fisch came on very clear and bright, and often too strong, overplaying Skelton. His second, and their last, performance he pulled way back and Skelton had a better time of it. Rattle at the movie was a rounder sound, while clear and true.

Nina Stemme, in her nearly 100th performance and Stuart in his first [at the Met Opera – Editor], were wonderfully and quite incredibly matched, as old timers Rene Pape as King Marke and Ekaterina Gubanova as Brangäne and newcomer to the role of Kurwenal Evgeny Nikitin were richly and well played. I was surprised and delighted to note the small differences in the individual performances over the three productions, in the movements, the acting, the expressions and even the voices of the singers. The orchestra was more of a complete perfection in detail, in every performance.

I was also surprised to confess how much I appreciated the film version. The interviews, while superficial, are revealing and sympathetic and informative—what fun to meet the Puerto Rican English Horn player! The close-ups and angles of the filming are often more interesting than—in this case—the very dark uninteresting staging. We are fortunate to live in a world where such performances of the highest calibre are offered. As our Stuart Skelton said, twice, in his interview, "I am a very lucky boy!” We, too.

Then I recalled the production at Bayreuth last summer [2015], the production itself completely forgotten, visually as unmemorable as that of the Met. However, I do remember feeling emotionally drained, people all around with tears running down their faces, and wondered at the lack of emotion, or much less, of the Met performances. In what part of an opera performance does emotion lie, from whence does it come? The music is sublime and contains all, but is it the singers, the conductor, the director who draws out the tears? A couple of years ago, there was a concert performance in Auckland and I must say, the opera really does well without the crazy, distracting complexity added by so many directors, which is a further recommendation for the Stemme/Skelton performance in Hobart later this month.