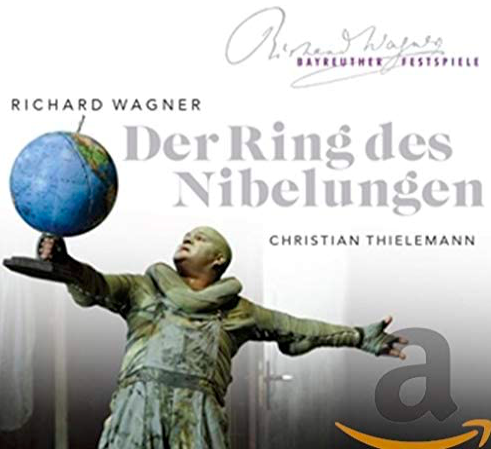

Brett Johnson recollects Bayreuth 2009

Bayreuth Thursday 20 August 2009

Thirty years after my first, and until now my only Bayreuth Festival, thanks to the Wagner Society, I’m typing this in my room at the Hotel Goldener Hirsch a few hours before Rheingold begins.

This morning, I went to the first of the Wagner Society of New York’s lectures by Professor Hans R Vaget. I had been impressed by his explanation of the synthesis of Bayreuth production history and German history more generally in last year’s new Parsifal, which Roger helpfully mailed with the tickets. It seemed to me that if we were in for Regietheater at full bore, some guidance by Vaget would be helpful.

The professor did talk about Regietheater this morning: Wagner as the pioneer “Regiesseur,” directing the first complete cycle and finding it necessary all the time to experiment; the famous exhortation to ‘make new things’. The professor opined that there was good and bad Regietheater. Good illuminates, bad merely follows a concept. I was glad to hear his views on current productions: he has, for example, ‘little regard’ for Katherina Wagner’s Meistersinger.

But what about today’s opera? Not an evaluative word or phrase, unless Vaget’s description of director Tankred Dorst as a ‘playwright’ had a barbed twist to it. I wanted to ask: What about this Ring production? Good or bad Regietheater? What’s Dorst’s main innovation, in your opinion?

I was too timid, however, and let others ask their questions. Back in my room, an email had arrived from an opera singer friend who saw last year’s Ring dress rehearsals. He really liked Thielemann’s Ring. No mention of Dorst.

After Rheingold

The curtain parts and it’s the bottom of a river. There are boulders – lots of them – in a broadly sweeping arc across the stage, with a projection above suggesting the curve and surface of the river. How literal and refreshing, I thought. The characters are going to clamber over rocks. Thirty years ago it was the infamous hydro-electric dam.

Disappointment soon sets in: the gaudily red-costumed Rhinemaidens remain seated centre stage for almost the entire scene, languidly waving their arms. Body-stockinged nymphs appear and disappear among the rocks, teasing Alberich, while naked nymphs appear on the projection above, as though swimming on the surface of the river.

It’s all naively untheatrical. If the Rhinemaidens don’t act out their mindless, erotic, tactile, teasing games with Alberich, where’s the sexual spark that sets off the frustration and the vengeance to come?

The trio’s singing, however, was clear and perfectly in tune, benefiting from Thielemann’s unhurried and flexible approach, which becomes a hallmark of this conductor’s Wagner. The Alberich is stretched by the vocal challenges of the role and, with no real contact between him and the Rhinemaidens, fails to make much of a dramatic impact. Instead of rushing off at the end of the scene, he remains fixed centre stage clutching a piece of the ‘gold’ while the curtains slowly close. To sum up: the first scene reveals the director’s limited range of theatrical gestures, lack of faith in the acting skills of the singers and his disinterest in creating memorable tableaux.

As the performance unfolds, this lack of insight into what Wagner’s characters are about, or what an overarching view of the cycle might be, becomes more and more clear. In addition to directorial stasis, the great scene between Fricka and Wotan is hampered by two things: the singers are not up to the vocal demands of the roles – and their costumes. Wotan should have refused to wear his outfit, which looked OK when the left side faced the audience, a nicely-cut long coat, but on the other side, cut away to reveal his strange barrel body. Fricka’s close-fitting moulded costume with its short train appeared to limit her gestures to semaphore hand signals and small, petulant steps.

Scene two introduces the first of Dorst’s many pointless, though clearly thematic, Regietheater bits of stage business. During Fricka’s diatribe, a young man who might be seen in the streets of any modern western city, comes on, looks around, takes a desultory photo of some graffiti, and walks off. This diverts attention, of course, from Fricka, who is only just coping with the vocal demands of the huge role. Later, in Scene 3, another character from the modern world, a technician, comes on, casually checks some electrical gauges, and goes off. Right at the end of the opera, a child comes on and finds some of the Nibelung treasure, is attacked brutally by another child, while other boys abduct a young girl. All of this during Loge’s marvellous, sarcastic take on the Gods entering Valhalla, tonight over a non-existent (from my seat) Rainbow Bridge.

What is meant by all this Regietheater stage business? Perhaps the setting of the ‘historic’ main action in a modern world full of sometimes trivial, sometimes violent moments is meant to remind us how the mythic world led to the state of the current world, with its real people, like us, tourists with cameras, real (horrible) children. I wish Vaget had said something to help.

Friday 21 August: After Die Walküre

Finally, a Wagnerian voice in a main role. Eva-Maria Westbroek has got to be the Sieglinde of her generation. Not only is she extraordinarily beautiful, with a clear, luminous face, she seems exactly the right age and has a big, beautiful, powerful Wagnerian voice. Dorst does nothing particularly wrong, or illuminating, in Act 1. The ash tree is an electric power pylon that has smashed into a large cube-like room that seems semi- inhabited. The action begins with some children taking refuge from the storm. One of them whips back a sheet to reveal Sieglinde. There is no fireplace or fire, so Wagner’s detailed lighting directions for the sword will not be relevant. Hunding arrives with five henchmen, who are not given anything to eat and retire at an appropriate moment. Siegmund is great to look at – short and chunky, with delightfully northern, dirty blond hair, stubble, and sweaty torso. From his first phrase, however, we know we aren’t going to hear one of Bayreuth’s great Siegmunds but, as ever in the cycle so far, Thielemann works closely with the singer, capitalising on the singer’s strengths and minimising dangerous exposed moments. His inadequacy is most obvious in the final scene with Westbroek, where the contrast between her large luminous voice and his much more modest resources is stark.

Again, the director simply seems uninterested in final moments: the lovers don’t rush off, there’s no sense of passion about to be consummated. The singers’ dependence on the conductor, whether straight ahead or sideways at monitors, did nothing to raise the emotional temperature. I am perplexed by the level of insecurity this dependence revealed. It is, after all, the third cycle of the fourth year of this production. Perhaps in the face of inadequate direction, singers become more dependent than they otherwise would on the conductor, the one holding the show together. A more experienced director would surely incorporate key moments of eye contact with the conductor more naturally into the action.

As for Regietheater business, during Fricka’s great scene with Wotan, two men bring in a trolley of suitcases. The sound of the trolley rumbling off the stage really annoyed me. This is one of my favourite scenes in the Ring. As I mentioned, she is not really a Fricka vocally – a sign of the vocal times here at Bayreuth – but more than getting through the role thanks to a solid, intelligent technique. Only a sadistic, or clueless, director would divert our attention during this marvellous stretch of music drama with bits of mystifying, inexplicable stage business.

Then again, there was some major coups of theatrical and musical passion. ‘O herstes Wunder’ was one of them, with Sieglinde almost centre stage, close to the front, arms wide apart, a piece of Nothung in each hand, Westbroek filling the theatre with her huge voice, coping with Thielemann’s slow speed almost completely, a moment when Thielemann wrongly equates slow with intense.

March 2022

It’s pretty negative, isn’t it? I recall thinking, after Rheingold, that there is something seriously wrong with the casting if the best Wagnerian voice is Freia (Edith Haller).

The other roles and singers: Alberich (Andrew Shore), Siegmund (Endrik Wottrich), Wotan (Albert Dohmen), Fricka (Michelle Breedt).

I recommend Anthony Tommasini’s review of the first year of this production in the 2 August 2006 New York Times, in particular, for his comments on the limitations of Dorst’s production. Dorst famously did not return to Bayreuth after 2006 to fine-tune the staging.

https://www.nytimes.com/2006/08/02/arts/music/02ring. html#:~:text=Before%20agreeing%20to%20take%20 on,one%20exception%3A%20direct%20an%20opera.

Apart from the Ring, the Wagner Society group was treated to Die Meistersinger in which Walther was an artist sloshing huge amounts of paint around, Tristan und Isolde in a fascinating, static production by Christoph Marthaler, tepidly conducted by Peter Stein, and the extraordinary Herheim Parsifal, which remains the most expensive-looking production I’ve seen anywhere, ever. I strongly recommend fellow-pilgrim Jim Leigh’s insightful article on this in the Views and Reviews section of the Society’s website: https://wagner.org.au/index.php/views- reviews/review-redemption-ten-dimensions-stefan-herheims- bayreuth-parsifal-201

From the Wagner Quarterly, June 2022