By Terence Watson

Director, Moira Blumenthal; Michael Misrachi and Michael Shur, Producers; Set & Costume Design, Hugh O’Connor; Video Design, Mic Gruchy; Lighting Design, Emma Lockhart-Wilson; Sound Design, Katelyn Shaw.

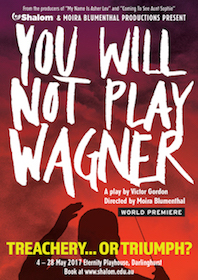

Cast: Annie Byron - Esther (conducting competition founder and sponsor); Tim McGarry - Morris (competition administrator and close friend of Esther); Benedict Wall -Ya'akov (Israeli conductor and competition finalist); Kate Skinner - Miri (competition assistant/assistant to Esther); Graham Bruce - Richard Wagner Consultant); at the Eternity Theatre with the world premiere produced by Shalom and Moira Blumenthal Productions.

The Director's program notes say: "The play opens in November 1938, during the Night of the Broken Glass, Kristallnacht [depicted with historical video footage projected on the back wall of the theatre], moves to London during the late 20th Century and then to Israel at the cusp of the new millennium." While the video footage during the opening provides graphic and immediate scene and emotional setting, and similarly when repeated at other points in the play, the latter movement is, though, not clear from this production: I assumed all the contemporary action was happening in Israel now.

That aside, the play is based on the proposition that Esther has, from some years after World War II, committed some of her apparently large wealth to an international conducting competition in Israel. This year, for the first time ever, a young Jewish Israeli conductor has made it to the finals. Esther and Morris meet late at night after the announcement of the finalists to celebrate Ya'akov's success, but their pleasure is short-lived. They receive news that one of the finalists has chosen to play a selection of Wagner's music: they both exhibit their prejudices and preconceptions by assuming that it must be the German finalist who has dared to provoke the judges and the citizens of Israel. It is, though, Ya’akov who has chosen to conduct Wagner, not, as he later explains, because he specifically wants to challenge the unwritten ban, but because, during his training in Berlin, he was overwhelmed by hearing the opening of Das Rheingold. Wagner's music is now central to his life as an artist and a person. The rest of the play is largely concerned with Esther and Morris trying to persuade Ya'akov to choose another composer's works—his Mahler, they both attest, was transcendental. He refuses, and points out that the competition rules do not contain a prohibition on Wagner's music being played during the competition.

At this point it becomes clear that the competition can be taken as a metaphor for the attitudes to Wagner and his music in Israel generally where the ban on Wagner's music is also tacit; it is just understood that no one would reasonably choose to do such a thing. Ya'akov points to the instances of Zubin Mehta and Daniel Barenboim playing a piece of Wagner's music, with some protests from some sections of the audience, but support from other sections. These precedents cut no ice with Esther or Morris. These two older characters are balanced not just by Ya'akov, but also by Miri, the young assistant who appears now and again in the play, to represent, perhaps, an apolitical, ordinary Jewish person who understands the pain of the survivor generations, but does not feel them to be particularly relevant to her life—until Esther recounts another episode from her younger days in Nazi Germany and Miri comes to understand some of Esther's deep continuing pain.

Morris is forced to admit, with bad grace, that it was his mistake not to include an explicit ban in the rules, but he protests it should be understood by any Israeli musician that it is not acceptable to play Wagner’s music, at least while there are Holocaust survivors, or their children, still alive to be further traumatised by the performance of music that arouses hideous memories of their past, or their parents' past. Ya'akov defends his choice by pointing out, for example, that he is a child of survivors as well, but he has been able to overcome his "indoctrination" through personal experiences and growth. Esther and Morris bridle and accuse him of shocking insensitiveness for a Jewish person. Ya'akov seemed to me to be intended as a representative of a new, independent, confident generation of artists not wanting to be constrained by history, with the older Esther and Morris constrained by their histories and responsibilities.

At this point in the play (about halfway through the 90 minute play and well after midnight in play time), it seems that there can be no common ground, so they all agree to meet again later that day to talk further. The next day, Ya'akov offers further arguments supporting his position: the music is pure (Esther counters that he cannot legitimately divorce the text from the music—ironically, Wagner's own position); and so many people in Israel drive German Mercedes Benz cars, so they are hypocritical and their objections to Wagner and his music are inconsistent (Esther counters that there is a world of difference, given the help post-war Germany has been giving to Israel); Ya'akov contends that, while there is anti-Jewish content in Wagner's polemical texts, we can also choose to detach it from Wagner's artworks—they exist in the public domain where we can make our own choices about how to respond to them, the artist and his views. Esther contends, as Wagner did, that his text and music constitute a seamless whole, but she also insists that his artworks are contaminated by his personal prejudices. This latter point is the subject of much continuing controversy outside the play about the appropriate way in which to "deal" with the "Wagner problem."

Esther also laments the way in which modern (classical/serious) music has become just another industrial and commercial product—echoing unconsciously (I think) one of Wagner's major complaints in the essays he wrote in Zurich (Art and Revolution, The Artwork of the Future, and Opera and Drama). In those essays, he lambasts the corruption of the pure arts by profit and entertainment in terms very similar to Esther's.

As the play moves to its conclusion, Esther makes a very personal plea to Ya'akov to reconsider by telling her own experience as a young child in Nazi Germany, in various concentration camps, losing her parents, and surviving— just—to arrive in America and to a better life. Ya'akov is, of course, moved by her story, but he still says he is determined to conduct Wagner's music because of his commitment to his art. His position echoes that of Wagner who also refused to compromise his artistic and aesthetic visions to make his life easier.

There is also a subplot involving the theft by Nazi thugs of the very young Esther's treasured Stradivarius (?) given to her by her father. During the play she receives mysterious, but clearly disturbing, phone calls from Sam, that are finally revealed just before the play's end to be him reporting the successful retrieval from an auction of the violin and its imminent return to her.

As a kind of coup de grâce, she reminds Ya'akov that the finals will be held on Kristallnacht and leaves him alone on stage. He turns weeping to the audience and the stage goes dark, leaving the audience with no explicit resolution: in other words, it is up to the audience to decide how they would behave in these circumstances. The audience reacted very positively to the play and performances, but there was a chastened, somber mood amongst us as we left the auditorium.

The performers were convincing in their portrayals of complex characters trying to negotiate very fraught situations with humanity. Tim McGarry, as the administrator Morris, is faced with the potential implosion of the competition, and so tends to be acerbic and bullying in his dealings with Ya’akov, but he is also compassionate and protective of Esther. Annie Byron as Esther maintains an almost regal persona, reflecting her wealth and status, but often shows how there is deeply conflicted human being under the persona with mercurial changes from humour to pathos to anguish. Benedict Wall gives his Ya'akov a certain detached, ironic persona not uncommon with younger people still trying to make their mark in life, but, once challenged to reflect on his decision, he reveals a capacity for empathy that bodes well for his future as a thought-provoking conductor. Kate Skinner as Miri has no great significance in the play, but her presence is used at times to break a tense situation, or contrast with Ya’akov’s intensity, or just serve as a factotum for necessary stage business. However, she carried these various functions effortlessly and sensitively.

It is not made explicit during the play that many of the "Jewish" musicians, composers and other artists (Mendelssohn, Meyerbeer, Heinrich Heine, for instance) felt compelled to convert to Christianity to have a career in any of the German court services. In a sense, this is a betrayal of their obligations to their birth faith, but from another perspective they can be defended as making practical decisions to make a living. This of course does not excuse those "Christian" courts of their bigotry in imposing such prescriptions and proscriptions on Jewish people. However, the play does not seem to advert to this complicating factor in Jewish-German history, but it does raise an echo in Ya'akov's struggle to carve a career as an artist through the difficulties of modern life with so much competition from other aspiring conductors. Of course, many such subjects could not be covered in detail in a one act play.

As I thought about the play later, it occurred to me that there was an even greater irony in the general proposition about mounting a conducting competition in Israel that was not explicitly explored. The orchestra, which is the "instrument" that the aspiring conductors are "playing" in their pursuit of a career, is largely the creation of German musicians during the hundred years from, say Haydn to Mahler; the size, range, flexibility, instrumental innovations, etc that happened largely in German states, though not without contributions from Jewish musicians and composers. So the competition is focused on a more or less entirely German cultural creation of at least as great a, and I would argue greater, significance than any model of motor vehicle or other material product produced in Germany and exported to Israel.

If one were cynical about this situation, one could suggest that the modern orchestra in Israel is a kind of fifth column both infiltrating Israeli culture with great, and "acceptable," German masters and determining the manner in which it is performed and the means by which it is performed. We do not, of course, generally conceptualise "the orchestra" as a product, cultural or technological, let alone the history of its creation and distribution around the globe as a mechanism for disseminating a repertoire that is very heavily freighted with universally acknowledged geniuses of music-making, a large proportion of whom are German. In this context, the discussion of whether or not various composers - Chopin, Stravinsky, Orff - were anti-Jewish or anti-Semitic seems to be a sub-category of a larger question about the creation and perpetuation of racial and other stereotypes within our prized cultural institutions.

We could perhaps also justifiably speculate that some members of the orchestral instrument on which the aspiring conductors are "playing" in this competition are Germans, performing side by side with Jewish musicians and musicians from around the world. Indeed, probably all modern orchestras are multicultural institutions, with even the once most tradition bound ones now admitting women and "foreigners" into their ranks - and arguably producing even better playing than their earlier, "purer" manifestations. It is thus a little disappointing that none of the characters in the play addresses this fact and that the playwright seems not to have even attempted to point to this greater dramatic irony.

These reservations aside, the play is definitely worth seeing and I wish it well in finding many more performances around the world.

You can read Victor Gordon’s account of his motivation in writing the play at: www.limelightmagazine.com.au/features/question-performing-wagner-israel. You can read further reviews and articles at: www.jewishnews.net.au/reigniting-wagner-debate/64279; and www.jewishnews.net.au/can-one-play-wagner-clear- conscience/63977; www.jewishnews.net.au/62817-2/62817.