Live, New York, Thursday, 30 September 2010

By Richard Mason

Live, New York, Tuesday, 5 October 2010

By John Collis

Dendy Cinema Screening, Canberra

By Ian Cowan

New York, Thursday, 30 September 2010

By Richard Mason

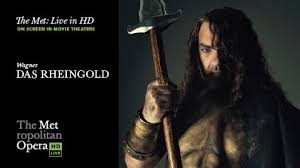

Lisette Oropesa [Woglinde], Jennifer Johnson [Wellgunde], Tamara Mumford [Flosshilde], Eric Owens [Alberich], Stephanie Blythe [Fricka], Bryn Terfel [Wotan], Wendy Bryn Harmer [Freia], Franz-Josef Selig [Fasolt], Hans- Peter König [Fafner], Adam Diegel [Froh], Dwayne Croft [Donner], Richard Croft [Loge], Gerhard Siegel [Mime], Patricia Bardon [Erda], Conductor James Levine, Producer Robert Lepage, sets Carl Fillion, costumes François St- Aubin, lighting Etienne Boucher

This performance marks the start of the first new production of the Ring at the Met in more than 20 years. For 6 separate seasons the beautiful, intensely controversial (hated by newspaper critcs, loved by artists and wildly applauded by audiences) Otto Schenk production has attracted Wagnerites from around the world. The new production represents a huge gamble by Peter Gelb and the Met, with new stage machinery costing up to $40m by some estimates, necessitating a reinforcement of the Met’s stage.

Prima la musica. James Levine, having suffered ill health and cancelled engagements for some months, created an intensely beautiful, sensitive and dramatic account of the score. Levine managed to accommodate the singers’ vocal lines and a lyrical approach with a motivic energy, moving forward like a gigantic flywheel. His hand movements showed a careful concern with balance, as well as sensitively cueing the singers. Many details in the score were revealed: one stand-out was the blood- curdling horn trills following Alberich’s curse.

The singers were of a generally high standard, with 2 exceptional performances. Eric Owens [Alberich] created a strong character with much greater range and development than usual. In the opening scene he was playful, then tempted by the gold after his rejection by the Rhinemaidens; in Nibelheim he became a megalomaniac; in his curse he achieved a tragic dignity. Stephanie Blythe [Fricka] has an exceptionally rich, strong instrument with which she created a rounded characterisation of a wronged wife trying to repair a broken marriage. Bryn Terfel [Wotan] generated great hopes when he first sang Wotan in London 6 years ago. The voice is still distinctive and reasonably expressive, and is now much darker, but unfortunately bad habits [a Scarpia-surfeit?] have removed all traces of legato. His Wotan conveyed limited emotion with a generic anger. Richard Croft [Loge] gave a fine, lyrical and at times beautiful performance, but was somewhat underpowered. Freia was a touch shrill and occasionally sharp, Erda had a piercing vibrato, appropriately doom-laden, the giants were strong and individually characterised. Gerhard Siegel [Mime] was well-chosen for a small role, and, both musically and with character, pointed towards Siegfried.

Poi la scena. The production was dominated by 24 planks (technically, rhomboids) which filled the entire rear 3⁄4 of the stage. This device, termed “the machine” by stagehands, could be lifted up and down, and each plank could be individually rotated. In addition, video projections were used to make the machine resemble the bottom of the Rhine (flowing pebbles through which Alberich scrambled), giant hands on which the giants stood to make their demands, the cleft leading to Nibelheim (Wotan and Loge doubles walked on a vertical wall), the roof of Nibelheim (glittering gold- bearing rock) and finally Valhalla (god doubles ascended a vertical rainbow bridge, which then closed to form a drawbridge and finally a wall – the gods’ refuge from the world and their prison from reality). The obvious danger with technology is to play with it too much, distracting from stage action and narration. [Anyone who saw La Damnation de Faust from the Met by the same director, with a bank of video screens illustrating the action, will recognise the extreme dangers of this approach]. However, worst fears were not realised, as during scenes the machine was relatively static, movement being largely confined to the transformations – this had the distinct benefit of suppressing the Met audience coughing fit which invariably accompanies these – the Master would have approved. Perhaps erring towards the generous, it is possible that the machine will provide a unifying factor drawing the entire cycle together. The main drawback with the machine was to confine most of the action to the front 1⁄4 of the stage, simulating a concert performance at times. In addition, it was quite noisy. Interestingly, the costumes would have fitted without alteration into the Schenk production, and the Tarnhelm appeared identical. There were unfortunate technical glitches: on opening night the gods could not ascend the rainbow bridge, and at this performance the top of Wotan’s spear fell off when he confronted Donner. This might have been taken as an emasculation symbol, pointing towards the spear’s eventual destruction. However, it was an error: when Wotan’s double appeared, his spear was intact, but when Bryn Terfel returned, the spear lacked its point. As described above, there were some interesting and novel characterisations, and the production avoided both Eurotrash pyschosymbolism as well as Schenk naturalism. It passed the ultimate test - the Master would have been entertained, apart from enjoying the extravagance in these austere times.

Final verdict – conducting excellent, singers very good, production good.

New York, Tuesday, 5 October 2010

By John Collis

[John is a resident of Brooklyn, although originally Australian. While he has seen many productions of Wagner’s operas over the years, his primary musical interests lie in a much earlier period – Renaissance and Baroque. However, John is also a singer and so his comments about Wagner’s vocal writing come with some authority, if from a different perspective. Ed.]

James Levine conducted, but had to be assisted to the podium and did not climb up on the raised stage for a bow, remaining on the side and waving the singers forward. He looked very thin, so it was rather remarkable that he was able to conduct for 2.5hrs without a break!

It’s always a pleasure hearing the Met orchestra, especially when there is so much symphonic writing throughout the piece. They played very well, with some quite marvellously stirring moments. The opening passages were so beautiful, not a fluff or a beep from the horns. The singing was also generally very good: the Young People playing the smaller roles were determined to be noticed and to show some flair, so there were some great moments from them (i.e Donner and the lightning at the end). Stephanie Blythe has such a horn of a voice that the clarity was stunning, even above the orchestra. Such a pity there were not any extended arioso passages for her so that we could have enjoyed her more.

The two Germans who played the giants were equally as impressive and managed two rather different vocal sounds well, as they played off one another (as much as they could given the constraints of the set). One expects this from the Met, especially in such an important inaugural production. Bryn Terfel also sang well, but I got kinda bored by his tonal style, which never seemed to vary much in colour or volume. I reckon such a big part, with so much storytelling and carrying the action forward, should be given with a lot of different flavours. Maybe not all his fault, however, as the movements and acting directions seemed pretty minimal and stand-and- sing, especially for his part. The Mime was good, but hampered by a rather weird outfit (more later). The Loge, Richard Croft, a local boy, took about 5 mins to warm up then sounded great! Again, though, the voice had only one or two colours and I really wanted more for this centerpiece of the drama, who has so much influence over the action (and who represents fire for goodness sake!). A few more snarls, a few more fluted high notes would have made the world of difference. His acting was fine - he had a lot to do on a very awkward stage, but the singing, while not dull, was also not varied enough for me. This was most certainly not the case with Eric Owens as Alberich. He stole the show, I thought, just by being the part without affectation. He never tried to make a “character” voice, but gave us so many colours and was not afraid to inflect his pitch for a thespian effect. Hands down the best singing of the night! (The New Yorker agrees with me!)

You will remember that the “philosophy” behind this Met production is to blend the new theatrical devices with 19th Century production values. Costumes were kinda Star Trek (next generation Klingon), but I could see the attempt to use the old ideas of pre-historic Nordic outfits. The ladies and the gents were, on the whole, in skirts. Gnomes were in one-piece jump-suits with attachments (Mime had this full

frontal apron flapping about) and Alberich wore one in (of course!) gold. Maybe this was in the original production, too? Loge was in an off-white outfit of wrapped-cloth- with-leggings, which played well in his special fiery follow spot (which only worked in one horizontal position on the stage - very silly as he moved in and out of it). He did have special-effects hands with lights that were used to clever effect, though sometimes I wanted them off, as they were distracting. Wotan, of course, had a Funny Wig with hair over the blinded eye. Gave him an opportunity for head tossing (curls and all).

The set was a Great Machine. It creaked, it groaned, but did produce marvellous effects. Very 18th Century! Many of these effects were generated by the use of safety lines, so that we could get a “top-down” view of the action (shades of Esther Williams). These kinds of effects were foreshadowed in the circus or in the opening of China’s Olympic Games. That’s not a bad thing per se, but just everybody but the gnomes got to do a bit of wall-walking. The interactive video scenic effects were mostly B&W, but interesting nonetheless. Lots of cloud or riverbed movement, of course, as the actors moved about on the stage(s). Orange creatures for Alberich’s cave reflecting the hoard, which lay about in neat rows behind the forges. Pity no one on stage attempted a bit of [anvil] banging. It was hard to see where the clanks were coming from (I suspect the violas). The Giants were placed on evenly divided groups of planks with the gods on the apron stage below. This made both movement and interaction tricky, especially for Loge, who had to work the extreme rake between them. There was much sliding in the opening scene, too. Sliding was a [stage] motif, too, but did not appear to carry special meaning. The descent to Alberich’s cave was suitably spectacular as the Great Machine turned this way and that to make a Great Staircase. The trouble was that the safety lines kept getting in the way of the video (same with the Rhinemaidens). At the end, all the gods took a walk on the chintzy rainbow bridge, tied together with ropes that were entirely visible because they were so thick. As they were walking up a vertical wall, it was understandable but....tied together??

A problem I had with the whole opera is that there was no extended vocal singing that was not part of the dialogue. I know that it’s the perfect expression of Wagner’s theories, but I longed for Ms Blythe or the cute young man playing Froh to burst into song for just a bit. We get some of that in the beginning with the Lovely Ladies (who were not hiding much - not so 19th Century as mid-20th Century nightclub breasty Chanteuses). I’m sure Mr Terfel or Mr Croft would have dazzled us with their lyric brilliance. That’s really what the Young People tried to do with their moments in the limelight. And maybe Mr Owens did just that with his own part, which is why I enjoyed his singing so much more. Such a fine collection of voices. Such a splendid setting and so much anticipation of fabulousness. Just left me feeling a bit underwhelmed. But I’m looking forward toDie Walküre next year, when the aluminium planks may be called to do even greater feats of circus magic.

Dendy Cinema Screening, Canberra

By Ian Cowan

George Bernard Shaw wrote of Wagner’s own production of Der Ring des Nibelungen, “One of his devices was to envelop the stage in mists produced by what was called a steam curtain, which looked like it really was, and made the theatre smell like a laundry.” Technology has advanced. Nowadays we have what has been dubbed the “Valhalla Machine”. It looks like a gigantic fence, but one that tilts and skews and changes colour; sometimes becoming a sky-like or watery backdrop, and sometimes a complex platform on which characters walk at alarming angles, and makes the theatre smell, metaphorically, of carpentry.

We’re talking here of the latest New York Metropolitan production of Das Rheingold, what Wagner called a Preliminary Evening to the Ring, more particularly the film of it shown at Dendy Cinema. I’ll hasten to say that, whatever criticism I may level at the production, the singing and the acting has my unreserved admiration. Predictably, the Metropolitan has provided an introduction in which Bryn Terfel as Wotan is interviewed by Deborah Voigt. ButDas Rheingold is Alberich’s drama, not Wotan’s. Wotan merely has sufficient time to identify himself as a greedy, dishonest, hen-pecked old lecher. Let us forget him for the time being. He will have his day in Die Walküre and his come-uppance in Siegfried. As for Deborah Voigt, she does not yet appear; we can look forward to her immolation as Brünnhilde in Götterdämmerung. This evening, as I write, it is the time of Alberich. There never was a better Alberich than Eric Owens. This really great dwarf deserves ten curtain calls at the very least. The rest of the cast, most particularly Richard Croft as Loge, should have five. What sensitive, decent male would not sacrifice gold for sympathy from one of those entrancing Rheinmädchen?

Back to laundries and carpentry. The problem for a producer today, Robert Lepage in this case, with all the facilities of modern technology at his disposal, is knowing where to start and where to stop, or in which order to start and stop. Some of the scenes might have been painted by Rubens. But then there is this extraordinarily mobile fence, which causes the audience, if not the cast, anxiety as to how to retain its balance. And there are the strange breast plates worn by Wotan, Froh and Donner. They demonstrate, as if to a class in human physiology, the pectoralis major, rectus abdominis and other muscles, all burnished, sometimes in bronze and sometimes in silver, to ensure that students and body-builders are unlikely to forget the images. Finally, after some three hours, towards the end, the lighting manager is unleashed. There is a riot of colour as the cast wends its way over the Rainbow Bridge toward Valhalla that could not have been bettered by Walt Disney. So we have here, in this production, a strange mixture of the traditional with the post-modern, the mechanical with the physiological, the sophisticated with the banal, which thankfully never overwhelms the glorious singing and orchestral playing. Nor does it displace the unseen, but overarching presence of the now frail, but always formidable maestro, James Levine

Shaw also wrote, “I must admit that my favorite way of enjoying a performance of The Ring is to sit at the back of a box, comfortable on two chairs, feet up, and listen without looking.” There are many moments in this performance of Das Rheingold when one would also be happy just to listen. Nevertheless, despite some misgivings, looking is well worthwhile